Envisioning Palestine

The Construction of a Jewish National Space

Zoltan Kluger (Foto): Rivka driving the hay rake at Kibbutz Maabarot. Government Press Office, 01.10.1940 Quelle: Flickr Lizenz: CC BY-SA 3.0

This dissertation project deals with the role of visual culture in the construction of Jewish Palestine as a political actor on the international scene during the 1930s and 1940s.

As active observers, photographers and filmmakers worked on the creation of different “visual referents” that would be recognized by their target groups. Rudy Koshar labelled the creation of such “referents” the “National Optics” of a nation state.[1] In contrast to former scholars who argued that these “referents” were created from within Palestine while its outer appearance was a side-product and “proof” of inner formation, I argue that the image of Palestine was created and shaped just as well for and by the foreign audiences observing Palestine and creating their very own “vision” of it. The work suggests that building the country’s national imagery should rather be seen as an international process than a national project. The nature of the visibility of Palestine in the Jewish and non-Jewish visual culture can tell us something about the role Palestine was assigned as a political entity and the assets it held for those who tried to make sense of this entity. Moreover, the gaze of these observers and their own visual reflections of Palestine can portrait the observing countries themselves through the relation they developed with this place.

The early 1930s present a favourable starting point for a study of this kind due to an increase of events that demanded visual illustration in the form of photographs and films, such as the growing conflicts between Jews and Arabs. Increasingly, both Jewish and non-Jewish groups asked for illustrations of the developments in Palestine. Significant for the increasing depiction of the processes in the Middle East was the birth and development of photojournalism and new facilities for the mass production of photographs and films.[2]

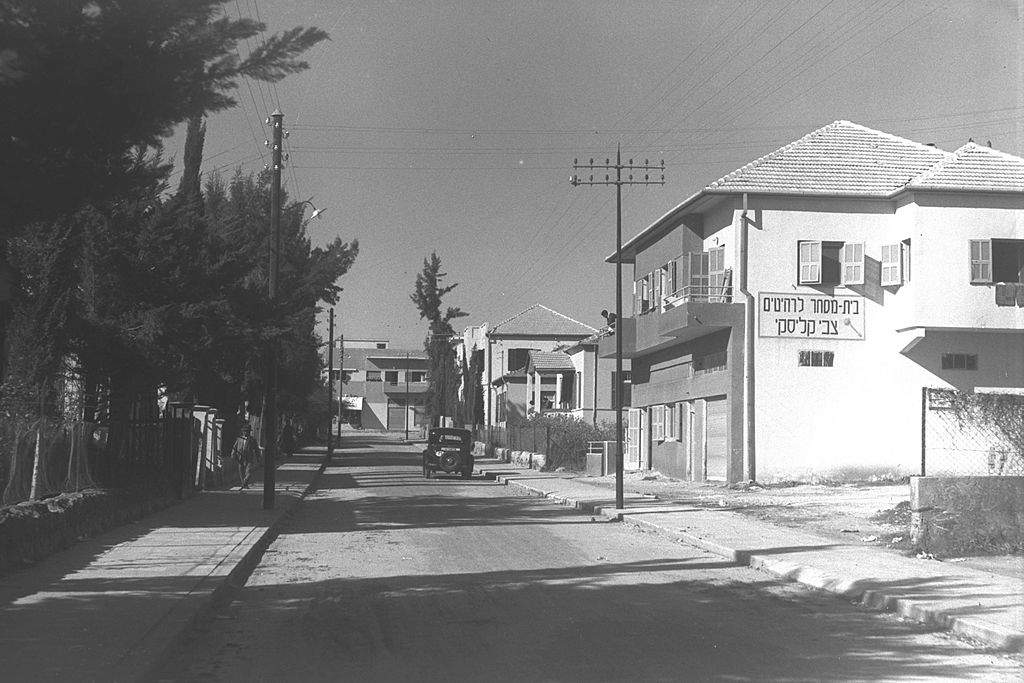

Zoltan Kluger (Foto): A street in Rishon Lezion in 1937. Israeli National Photo Archive, 01.02.1937 Quelle: Wikimedia Lizenz: Public domain or CC BY-SA 3.0

Two countries that made extensive use of visual culture, as means of political communication and propaganda were the United States and Germany. Both its national socialist government and its Zionist organizations were especially interested in the happenings in Palestine and both were leading in the use of visual culture as a medium for “nation branding”.[3] The different ideas of Palestine within both groups inspired and influenced the choice of motives and visual narratives in the creation of an imagery of Jewish Palestine.[4] While the non-Jewish makers of images from Palestine were interested in depicting Palestine as virtual threat to the German people, the Zionist institutions tried to “sell” Palestine as the future place to be for German Jews. Both groups, however, used the aesthetic photo-art of the Weimar German Neue Sachlichkeit to convince their spectators of the political nature of this Jewish space in the making. Much can be drawn from these images about the role Jewish Palestine was believed to play as an emerging political actor.

This study will focus on both the production and the reception of images of Palestine abroad. It will highlight three interrelated themes: the constitution of Jewish Palestine as a national place; the varying role this imagined place played in the international context; and the behaviour of the observing groups in Germany towards Palestine. In the work I will analyse the specific films and photographs for the messages they were thought to convey, the influence of various distributing agencies, and the reactions of the spectators to the produced imagery. With the help of sources like newspapers, diaries and letters referring to the different photographs and films, the interplay between protagonists of the Zionist project in Germany and non-Jewish recipients of their visual proofs of Jewish life in Palestine will be portrayed.

Zoltan Kluger (Foto): A young Yemenite nurse reading from a newspaper to new migrants at the Rosh Ha’ayin camp. Israeli National Photo Archive, 01.10.1949 Quelle: Wikimedia Lizenz: Public domain

At the core of this study is the emergence of a translational network of images. This network ultimately constituted the interpretation of Zionism in the popular imagination and among policy makers during the eventful decades that preceded the foundation of the State of Israel. It will offer new insights into the interrelation of global and local processes regarding Jewish Palestine as a political sphere interacting with the world scene.

All photographs for this article are by Zoltan Kluger, who was born in 1896 in Hungary. In the 1920s he came to Berlin where he studied the Weimar aesthetics of the Neue Sachlichkeit and worked as a photojournalist. In late 1933, he left Germany for Palestine where he applied his “new view” to his photographic works for the Keren Hayesod. He became one of the main national photographers that shaped the Zionist national picture canon of the 1930s and his photographs were published in various publications in Palestine and abroad.

[1] Rudy Koshar, Germany’s Transient Pasts: Preservation and National Memory in the Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill 1998,S. 23.

[2] Daniel H. Magilow, The Photography of Crisis. The Photo Essays of Weimar Germany. University Park 2012.

[3] On the relationship between Germany and the events and transformations in Palestine see for example Klaus-Michael Mallmann/ Martin Cüppers, Halbmond und Hakenkreuz: das Dritte Reich, die Araber und Palastina, Darmstadt 2007; Nicosia, Francis R., Zionism and Anti-Semitism in Nazi Germany, Cambridge/New York 2008. For the American realm see Richard Breitman/Allan J. Lichtman, FDR and the Jews, Cambridge 2013.

[4] For the idea of the “branding” of a political group or a state and its mechanisms see Axel Balzer/Marvin Geilich/Shamim Rafat (Hrsg.), Politik als Marke – Politikvermittlung zwischen Kommunikation und Inszenierung, Münster 2005;John B. Thompson, Political Scandal; Power and Visibility in the Media Age, Cambridge 2000. For the German context see Roel Vande Winkel/David Welch (Hrsg.), Cinema and the Swastika. The International Expansion of Third Reich Cinema, Basingstoke 2007; George L. Mosse, The Nationalization of the Masses. Political Symbolism and Mass Movements in Germany from the Napoleonic Wars through the Third Reich, New York 1977. Some of the similarities of Propaganda productions in these years have been analysed for example in Peter Zimmermann/Kai Hoffmann (Hrsg.), Triumph der Bilder. Kultur- und Dokumentarfilme vor 1945 im internationalen Vergleich, Stuttgart 2003, S. 74-104.